The same producers who impeccably executed Meghna Gulzar’s 2018 spy thriller Raazi seem to have taken a misguided detour with their latest venture, Ulajh. This new release, directed by Sudhanshu Saria and starring Janhvi Kapoor, appears to be the inverse of Raazi but falls far short of the expectations set by its predecessor. The film endeavors to blend the genres of thriller and drama, yet what unfolds is a convoluted plot riddled with pretentiousness and overblown dramatics.

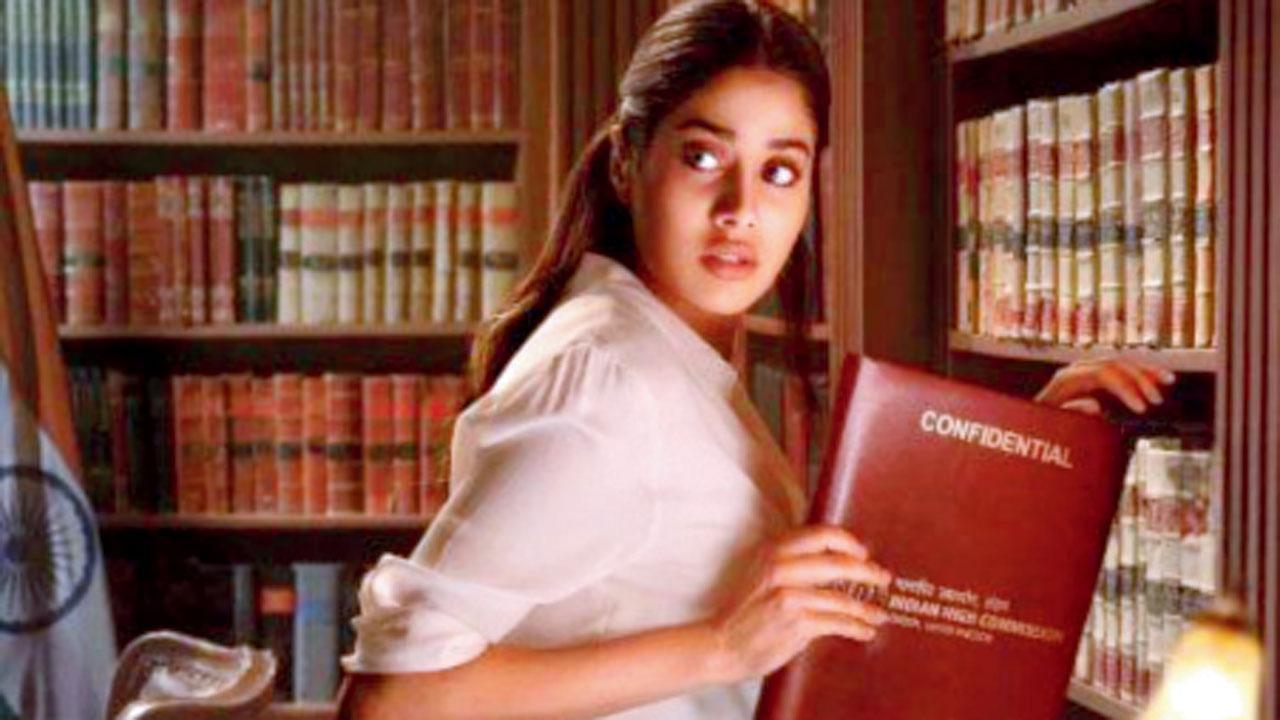

Ulajh boasts a visually impeccable protagonist, a young female diplomat named Rashmi Mehta, played by Janhvi Kapoor. The narrative establishes her as the youngest deputy high commissioner to Britain, a detail that sends Indian news channels into a frenzy and lays the groundwork for an exaggerated portrayal of international diplomacy. Rashmi is seen meticulously curating her outfits and navigating her opulent apartment and office, exuding an air more suited to a fictional US Vice President than a grounded Indian diplomat. Such implausible setups serve as early warnings for the cinematic turbulence that lies ahead.

As Rashmi steps into her high-profile role, she encounters hostility in her workplace, primarily from Roshan Mathew’s character, a defamed RAW agent. Mathew’s portrayal of an embittered colleague, driven by the believe in nepotism, is reminiscent of his previous roles as disillusioned young men, exemplified in the overrated art-house film Paradise (2023). His antagonism stems from Rashmi’s inherited privilege, a theme that mirrors the nepotism debate popularized in Bollywood but rarely scrutinized in other sectors.

Rashmi’s familial lineage is steeped in diplomatic legacy, with her father (played by Adil Hussain) being sent as India’s representative to the UN and her grandfather immortalized in civics textbooks. Such lofty credentials might evoke curiosity about the authenticity of the film’s portrayal of the Indian Foreign Service (IFS), but instead, it underscores the filmmakers’ apparent lack of research into the real workings of the IFS. This gap in authenticity extends to the film’s representation of global diplomatic engagements and the lavish lifestyles rumored to be funded by taxpayers.

Adding layers to this tangled plot is the involvement of the Pakistani intelligence agency, ISI, which blackmails Rashmi over a trivial incident, leading her into a deeper, less believable conspiracy.

. The narrative’s progression becomes increasingly difficult to follow, masking any semblance of a coherent storyline under the guise of ambitious writing. This complexity, rather than intriguing, becomes merely exhausting, leaving audiences struggling to remember the plot’s starting point or its direction.

One wonders whether the motivation behind this labyrinthine plot was the UK government subsidies for filming in London or the ostensible appeal of the spy-thriller genre itself. Despite the opulent London locales and detailed production design, the film feels hollow, relying on product placements like Pulse candies, which, ironically, deliver the most candid line in the script: “Pran jaaye par Pulse na jaaye” (Life may go, but not the Pulse).

The ensemble cast, despite their talents, are reduced to caricatures. Adil Hussain, Aly Khan, Gulshan Devaiah, and Meiyang Chang, each bring significant acting chops but find themselves adrift in a shallow script that offers little substantial material to work with. Their performances, though noteworthy, cannot salvage the film from its inherent absurdities.

Ulajh’s sound design and cinematography, though technically competent, oscillate between subtlety and overkill, contributing little to elevate the film above its many shortcomings. Midway through, viewers may find themselves diverting attention to peripheral recommendations like London’s restaurant scene, indicating just how disengaged the core narrative leaves them.

As we stumble toward an inconclusive and bewildering end, it becomes evident that the filmmakers harbor unwavering belief in the potential for a sequel. This misplaced confidence seems as bewildering as the plot itself, raising an eyebrow at the prospect of extending this seemingly misdirected narrative.

In retrospect, Ulajh presents as a curious case of misaligned ambitions and mismanaged execution. It attempts to capture the allure of an international espionage thriller but ends up ensnared in its own convoluted web, diverting far from the high benchmark set by Raazi. While the film aspired to high-voltage drama and intricate storytelling, it ultimately unravels into a perplexing maze, leaving viewers to navigate their way out with little more than bewilderment.