In a saga highlighting the intricate web of bureaucratic processes in India, playwright Imran Zahid finds himself ensnared in an administrative whirlwind after probing into the ban imposed on Pakistani films, including The Legend of Maula Jatt, in India. This inquiry, filed under the Right to Information (RTI) Act, has revealed more questions than answers, casting a spotlight on the convoluted workings of government ministries. As the debate over cultural exchange and legal ambiguity continues, Zahid stands as a witness to the complexities applicants encounter in their quest for clear information.

The inspiration for Zahid’s RTI quest stemmed from a deeply rooted admiration for Pakistani talent, embodied by actors such as Fawad Khan. Despite the limited opportunities to work in Bollywood, Khan has carved a notable fan base within India, prompting ongoing interest from filmmakers who hope to bring his cinematic creations across the border. However, these efforts are often met with opaque regulations and unpredictable obstructions, leaving many in the industry searching for clarity.

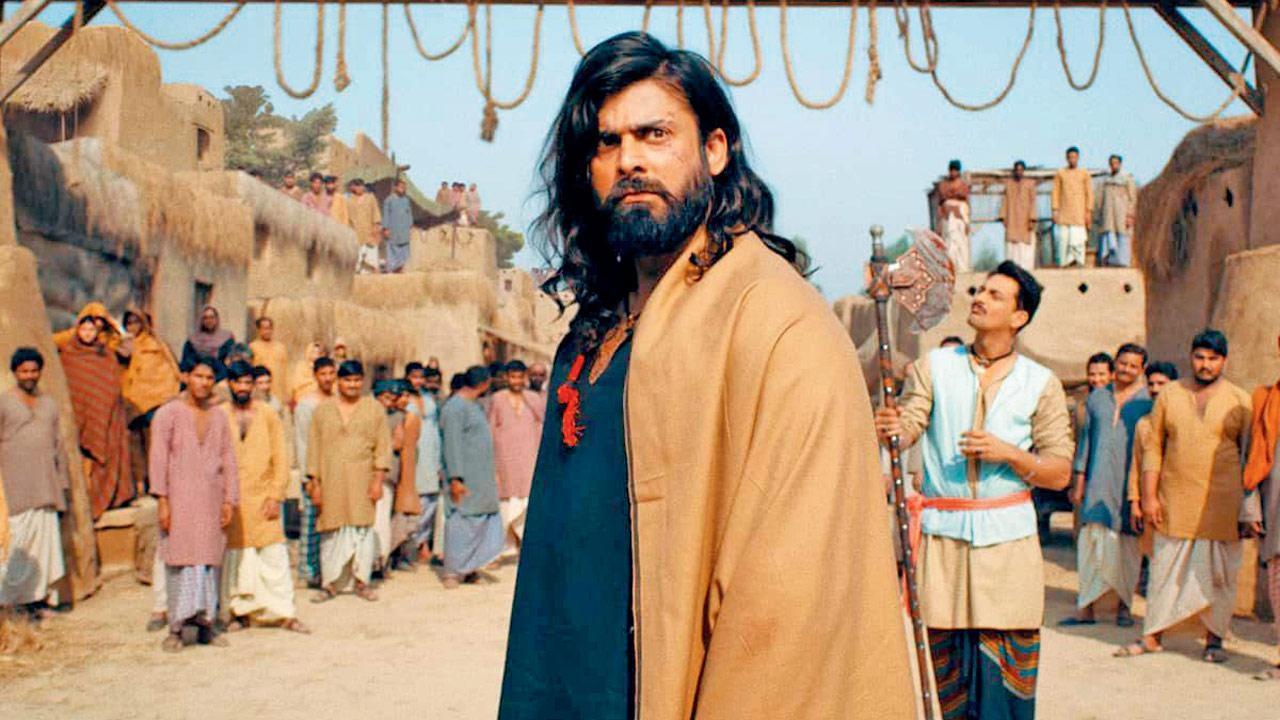

Zahid, who is ambitiously adapting the successful Pakistani drama series Humsafar for Indian audiences, found himself drawn into a bureaucratic maze after The Legend of Maula Jatt’s abrupt cancellation in India. His RTI application set out to demystify the legal landscape surrounding the exchange of cinematic works and artists between India and Pakistan. However, the experience has only highlighted the disarray within governmental avenues supposed to facilitate transparency.

Upon receiving Zahid’s RTI, the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) promptly forwarded it to the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (MIB), asserting that the latter was the rightful custodian of the matters in question. Such a transfer is mandated under Section 6(3) of the RTI Act when an application is erroneously dispatched to an incorrect department. Although the MEA followed protocol by issuing a new registration number for the inquiry, MIB’s subsequent response dismissed the responsibility, declaring a lack of authority on issues concerning foreign nationals and artists.

This cyclical redirection left Zahid in frustration, emblematic of a broader challenge faced by many who attempt to navigate India’s bureaucratic framework. Uncertain about the appropriate agency to address his concerns, Zahid voiced skepticism over the efficiency of the RTI process. His query, initially rooted in seeking clear legal standing, was seemingly engulfed by procedural paradoxes, prompting him to remark, “RTI is supposed to mean Right to Information, but it is coming across as Refusal to Information.

.”

The indecisiveness of the ministries is even more perplexing in light of recent judicial clarifications. In 2023, both the Bombay High Court and the Supreme Court of India ruled conclusively against any formal ban on Pakistani artists operating within the country. These verdicts were pivotal in quashing persistent calls from various industry groups and political entities for excluding Pakistani talent over security and patriotic concerns, post the 2016 Uri attacks.

The timing of the unofficial ban, traced back to tensions following the attacks, was perceived as a gesture of protecting national interests. Yet, court judgments have since rebuffed the notion that legal restrictions are justifiable under these circumstances, dismissing petitions from organizations like the Indian Motion Picture Producers’ Association (IMPPA) and the All India Cine Workers Association (AICWA).

Zahid questions why the lingering ambiguity exists despite clear judicial direction. “If there is a rule against Pakistani films and artists, it should be known upfront to avoid financial wastage on projects that may never reach fruition,” he laments, stressing the necessity for film producers to operate with certainty. Moreover, he questions the silence surrounding his inquiries, urging others to join in highlighting inconsistencies within cultural policy paradigms.

Amid these institutional challenges, Zahid’s dedication to completing the Indian rendition of Humsafar persists. His determination underscores the potential for artistic collaboration despite prevailing geopolitical constraints. He underscores that no such prohibition exists reciprocally from Pakistan, drawing attention to a 2015 clarification from MP Gen (Dr.) VK Singh (Retd) that Pakistani territory remains open for Indian artists.

As Zahid steadfastly presses on, a larger narrative of cultural diplomacy, artistic freedom, and bureaucratic impediments unfolds. His experience not only illuminates the struggles faced by those interacting with government processes but also ignites discourse on how cultural exchanges contribute to fostering mutual understanding—an element in dire need amid prevailing diplomatic discourse.