In a dramatic unfolding that raises questions about bureaucratic efficiency, renowned playwright Imran Zahid continues to grapple with governmental inaction over his inquiry on the ban of Pakistani films in India. Zahid, who is navigating through a maze of bureaucratic hurdles, has passionately pointed out what he perceives as the disarray and inefficiency in government responses, suggesting that the Right to Information (RTI) Act is boiling down to what he cynically dubs “Refusal To Information.”

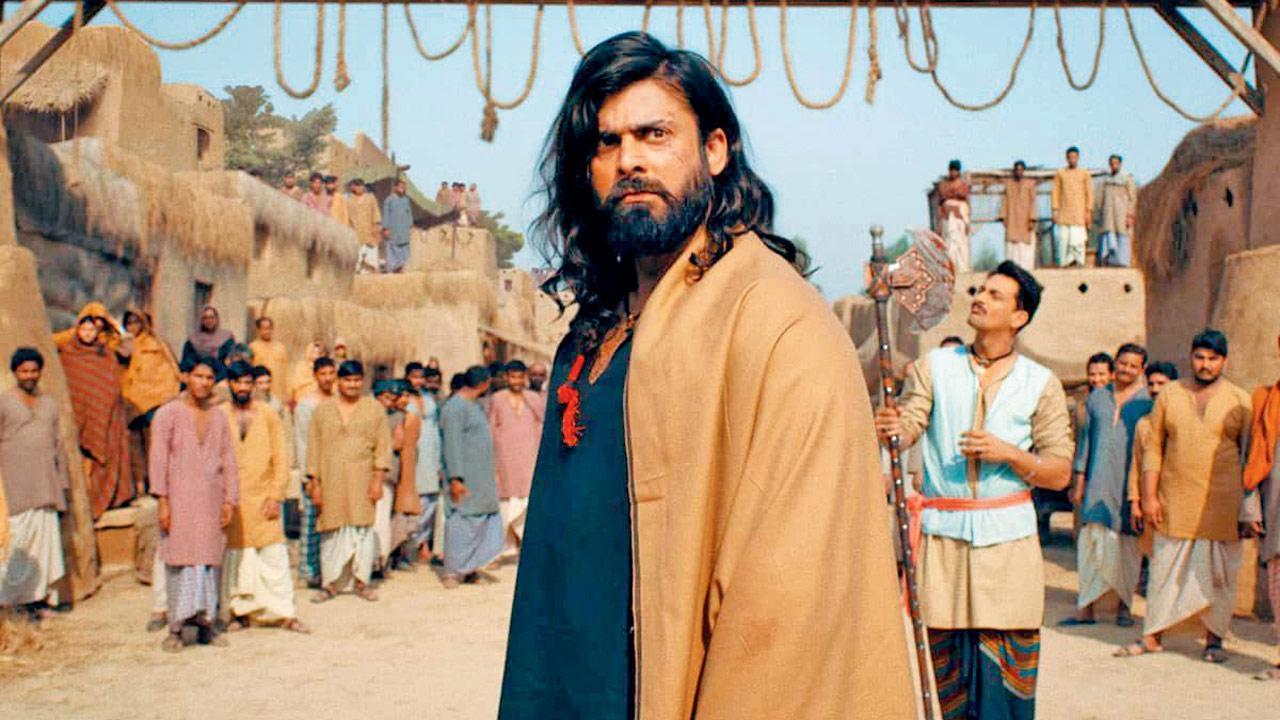

The debacle began when Fawad Khan’s much-anticipated film, “The Legend of Maula Jatt,” was suddenly barred from Indian screens. Despite the actor’s limited engagements in Bollywood, his popularity endures among the Indian audience, prompting filmmakers like Zahid to attempt releasing such content in India. Yet, these efforts are often thwarted by legal challenges that appear multileveled and surreptitious.

Delhi-based Zahid is not just a bystander. As a creative professional deeply embedded in transnational storytelling, he is working on an adaptation of the popular Pakistani television series Humsafar, featuring Fawad and Mahira Khan. With interdisciplinary collaboration becoming a global trend in entertainment, the continuous bureaucratic hurdles triggered Zahid to file an RTI application. His aim: to decode the policies governing Indo-Pak film releases and uncover the laws that pertain to artistic collaborations between the neighboring nations.

The RTI adventure took a convoluted turn when Zahid’s query was initially forwarded by the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) to the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (MIB). This was done under the obligation set by Section 6(3) of the RTI Act, necessitating the transfer of information requests to the appropriate governmental authority. Yet, the odyssey towards clarity did not end there.

“The initial redirection seemed encouraging, yet ultimately turned futile,” expresses Zahid. “After over a month, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting curtly informed me that restrictions pertaining to foreign nationals and international celebrity collaborations do not fall within their jurisdiction. This leaves me in a lurch, with no concrete answers, only contributing further to the bewilderment of creatives like myself,” he laments, pointing towards the indistinct policies that led to the unexpected halt of The Legend of Maula Jatt’s Indian release in 2022.

In his quest for transparency, Zahid is challenging the very handling of RTI applications.

. He raises critical questions about procedural responsibilities, particularly why MIB maintained his RTI if it lacked competency to address such issues. Moreover, Zahid questions the next step: which department, if any, offers a conclusive response when both the MEA and MIB seem ineffectual in providing clarity?

This state of bureaucratic entanglement appears even more perplexing against the backdrop of judicial pronouncements. Zahid underscores recent 2023 verdicts by both the Bombay High Court and the Supreme Court of India, which firmly stated that no legislative ban exists on Pakistani artistes working in India. “Despite these judicial clarifications, I find myself trapped in this bureaucratic back-and-forth, with RTI effectively standing for refusal to information, not the right to it,” he ruefully articulates.

Zahid’s exploration isn’t just about bringing Pakistani cinema to Indian theaters but also about guaranteeing creators know the landscape before investing in projects that might hit legal snags. He’s left wondering why these pressing questions aren’t being raised by others in the industry. “What are the actual rules and guidelines?” he asks, urging for transparency.

Adding another layer to the narrative, reports have emerged that a political faction in Maharashtra is threatening cinema owners who dare to show Fawad Khan’s films. This threat exemplifies the unspoken ban that exists unofficially, something Zahid suggests isn’t reciprocally present in Pakistan. He references past assertions, including clarifications made in 2015 and 2016 by then Minister of State for External Affairs Gen (Dr) VK Singh (Retd), confirming that Pakistan has not placed any blanket ban on Indian performers entering or showcasing their art there.

Reflecting on the timeline, the existing tensions are partly rooted in history. An unofficial embargo on Pakistani artistes took shape post the 2016 Uri terror aggression, with associations like the Indian Motion Picture Producers Association (IMPPA) and the Federation of Western India Cine Employees citing “security” and “patriotism” as the underpinning justifications for such measures.

Nevertheless, judicial opinions have resisted enforcing bans. The Supreme Court in 2023 shut down a plea to bar Pakistani artistes, reinforcing the Bombay High Court’s sculpture that non-statutory demands cannot morph into statutory prohibitions through legal endorsement.

In the ever-evolving discourse of art, politics, and society, Zahid’s case reverberates across borders, calling for an introspection into the operational frameworks that govern creative exchanges between countries, urging transparency and accountability in what continues to be a highly electrified and sensitive arena.